Systematically ferreting out value from great ideas has been a challenge. Often, the outcome is magical though. However, the scalability of ideas is at the core of nurturing ideas into Innovation successes. Ideas should be amenable to the addition of intellectual assets to increase the willingness to pay and reduce the cost. Otherwise, irrespective of the greatness, no idea succeeds in creating an innovation success story.

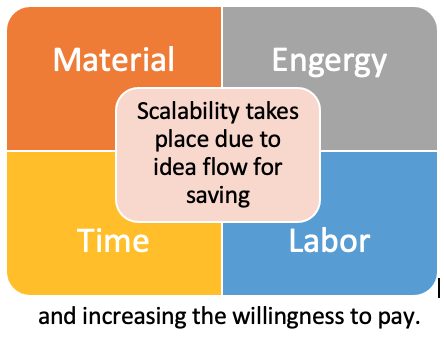

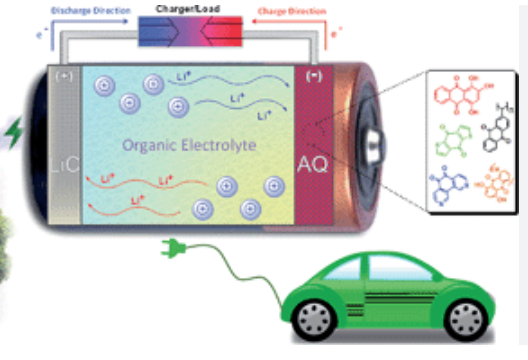

The scalability of ideas depends on their amenability of creating a willingness to pay and reducing the cost of material, labor, and other inputs in producing each copy of a great idea. The idea could be a lithium-ion battery or word-processing software. To leverage it, we keep adding intellectual assets to make a great idea succeed. These intellectual assets keep increasing the willingness to pay and decreasing the cost of objects—material, energy, labor, and others.

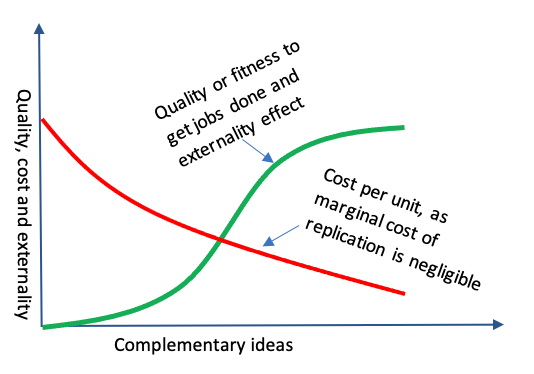

However, it also keeps increasing the R&D cost in producing and adding intellectual assets to the products and also the process to produce them. Hence, the scalability of ideas refer to the scope of keep increasing quality and not proportionately increasing, preferably redcuing, the cost per unit through additional Flow of Ideas. In a nutshell, meaning of scalable refers to the scope of increasing the quality and reducing the per unit cost through a flow of ideas.

Scalability of ideas in perspectives

Over the last 20 years, the price of the lithium-ion battery pack has been falling. On the other hand, the battery takes less time to charge—and also offers longer usable life. This is one of the reasons that smartphones are getting lighter. Due to less weight and the need for less time to charge, consumers’ willingness to pay is increasing. On the other hand, due to less material needed for storing the same units of energy, the cost of production is falling. However, to avail of these two effects, battery makers had to invest in R&D in generating ideas for better design of the battery and also for improved machinery to produce each copy. Hence, upfront R&D investment or capital expenditure has been reducing the marginal cost of producing each unit. In nurturing ideas, this is the genesis of the economy of scale effect.

Let’s think about word processing software. Forty years ago, PC-based word processing software was primitive. Consumers had little willingness to pay. Although the marginal cost, comprising the cost of copying software and distributing on a floppy diskette, was very low, the low willingness to pay among a small group of customers was limiting the scale advantage. Hence, producers started investing in R&D to add an increasing number of features for improving the willingness to pay among a growing number of customers. As the marginal cost was extremely low, the growing willingness to pay due to the addition of features and improvement of existing ones was driving the scale advantage. Consequently, the profit-maximizing price, at which marginal revenue equates to inframarginal loss, kept falling. This potential idea of increasing the willingness to pay and reducing the marginal cost is at the core of succeeding with innovation.

Production inputs and scalability

The basic definition of the economy of scale is about the decreasing cost per unit of production with the growth of volume. This is due to the fact that we divide the fixed cost over an increasing number of units. For producing a copy of a product, we need three major inputs: natural resources (ingredients, energy), labor, and ideas. We use ideas in the form of the design of the products and also capital machinery or tools. For producing each unit of the product, we have to pay the same amount for objects—ingredients, energy, and labor.

However, we do not need to pay for ideas for producing each unit. This role of an idea creates a scale effect. In the language of economics, we call this attribute non-rivalry. It means that the use of the idea by a unit of the product does not create a barrier to its use by another unit. For example, the same idea of producing mechanical motion by burning gasoline in a cylinder is in action in millions of cars. However, the material we use to make one engine cannot be used in making another. Due to this nonrivalry nature, ideas have an extremely high-scale advantage. This scale advantage is basically limited by the willingness to pay it creates and the marginal cost for objects in producing each copy of a product.

R&D cost, capital machinery, scalability, and monopolization

To have a scale advantage of ideas, we need to make an upfront investment in R&D to produce intellectual assets. For example, at the beginning of the Transistor’s life cycle, the quality was poor and the marginal cost was high. As a result, the scale advantage was low. Hence, innovators pursued the strategy of investing in R&D to produce additional ideas so that higher-quality of transistors could be produced with fewer materials, energy, and labor. However, many of those ideas emerged as Process innovation. Consequentially, the role of idea-intensive, increasingly complex machinery started growing.

Thus, the capital expenditure for setting up a semiconductor processing plant started increasing. Such growing capital expenditure also demands the sale capacity of a growing number of units to reach the profit maximization point. However, this trend of having the need for increasingly expensive capital machinery is not unique in the semiconductor industry. More or less, all industries, starting from automobiles to potato chips, are experiencing this trend. Hence, the scope of gaining market power for monopolizing the market has been growing. On the other hand, labor content has been falling.

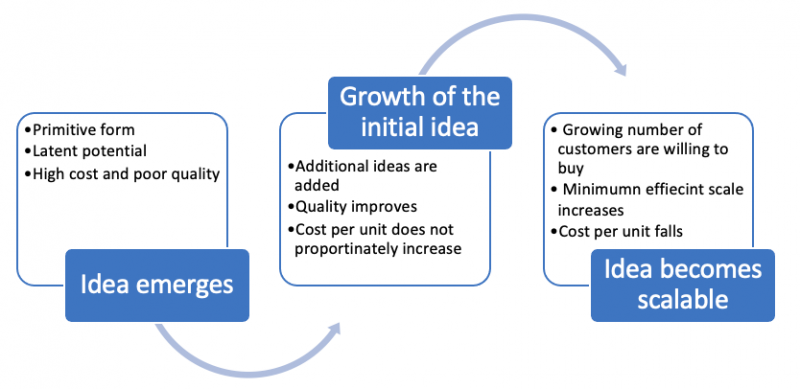

Innovation diffusion depends on scalability

Starting from mobile phones to digital cameras, irrespective of the greatness of ideas, innovations emerge in primitive form. On the one hand, these primitive innovations create very little willingness to pay among a small group of customers. On the other hand, the cost of objects is high, resulting in high marginal cost or low scalability. Hence, to empower innovations to diffuse, additional ideas need to be added to create a growing scale advantage. Besides, these ideas should keep increasing the willingness to pay among a growing number of customers—due to quality advancement. Furthermore, the need for objects in producing each additional unit should keep falling due to those ideas. That means that the marginal cost should keep falling. Hence, the diffusion of innovation demands the creation of a scale effect by adding a flow of ideas.

Scalability out of software

The software offers quite a high-scale advantage due to the fact that the copy cost of the software is zero. However, there is a high need for R&D investment in developing ideas for adding features and algorithms for creating the wiliness to pay. Despite the need for huge R&D costs, software innovation offers the scope of creating high scale advantage. The leveraging of this attribute has been at the core of making huge profits upon investing millions and selling the same software at a very low price—that is at a small fraction of the R&D cost.

Network externality and scalability of ideas

In fact, Microsoft, Apple, and others are recking huge profits by trading software for a few hundred dollars, for which they incur billions of dollar R&D costs. On the other hand, this attribute also creates barriers to those firms which cannot afford upfront high R&D costs. Hence, the software industry has a Natural tendency of monopoly.

Ideas could be added to create a Network effect for increasing the scale effect further. For example, Google and Facebook are befitting from the demand side scale effect, which is the network Externality Effect. Both of these companies have deliberately added features for creating the effect so that their products’ perceived value keeps growing with the growth of the customer base. Hence, innovations exploiting the supply and demand-side Economies of Scale have a far higher scale advantage. In fact, due to this effect, both Facebook and Google have become global monopolies in a very short period of time.

Complementary goods and services affect the scalability of ideas

The supply of complementary goods and services also affects scalability. For example, the availability of 3rd party apps through the app store has been contributing to increasing the perceived value of smartphones. The growth of infrastructure and compatibility also contributes to perceived value—thereby, scalability.

The scalability of ideas varies –affecting the scope of creating an innovation success story

As explained, scalability is at the core of creating an innovation success story out of great ideas. In the beginning, scalability is very low. The primary means of increasing the scalability is adding ideas to both the products and processes. The purpose is to increase the perceived value (leading to a higher willingness to pay), and reduce the need for objects.

However, all ideas are not equally scalable. For example, software-centric, innovative ideas have the potential to have a very high scale advantage. This is due to the fact that the marginal cost of copying software is zero. Furthermore, connectivity-centric software innovations also offer a demand-side economy of scale effect.

On the other hand, ideas that require material, energy, and labor to produce each unit of innovation have a lower-scale advantage. Besides, not all material-centric innovations have the same scale advantage. For example, silicon showed a high-scale advantage in making increasingly better transistors at a decreasing cost. However, there has been an increasing trend of adding ideas to create scale advantage in many material-centric innovations.

Scalability is at the core of succeeding with innovation. On the other hand, all ideas are not equally scalable through additional ideas. Hence, we should perform a careful analysis of the scalability of ideas to figure out the scope and strategy of winning with ideas.