High-techs or high technologies begin the journey in a primitive form, with latent growth potential. Hence, finding a growing market for High-tech products is quite unclear and often misleading. The high-tech market refers to winning the competition profitably and helping customers get their jobs done better through rapidly growing technology possibilities.

Unlike conventional products, innovators face tremendous difficulty finding customers at the beginning of a high-tech life cycle. However, the customer base grows over time, creating a large market. Is physiography of customers the underlying reason of time varying adoption of high-techs? The underlying reason has been the embryonic beginning of high-tech and continued advancement—making high-tech products better and cheaper. For example, in the very beginning, there were hardly any customers for personal computers, hard disk drives, LCDs, digital cameras, and mobile phones.

Besides, unlike hybrid seeds, the purpose of high-tech adoption by different customer groups keeps changing along the life cycle. For example, although hobbyists dominated the adoption of personal computers in the early 1980s, the mainstream market bought PCs for getting serious work done better. Such a reality raises the question of how to segment high-tech customers so that we can target them with suitable products at different stages of high-tech maturity.

Key takeaways

- inappropriateness of Rogers’ segmentation—based on the learning of how farmers responded to hybrid seed and other agricultural innovations, Rogers segmented the Innovation diffusion market; it was based on psychographic characteristics and risk management ability.

- uniqueness and economics are the underlying factors—unlike hybrid seed, high-tech innovations do not become instantly economically rewarding to all customers. Besides, high-tech innovations keep getting better and cheaper, making them increasingly attractive for adoption. Hence, uniqueness and economics play a vital role.

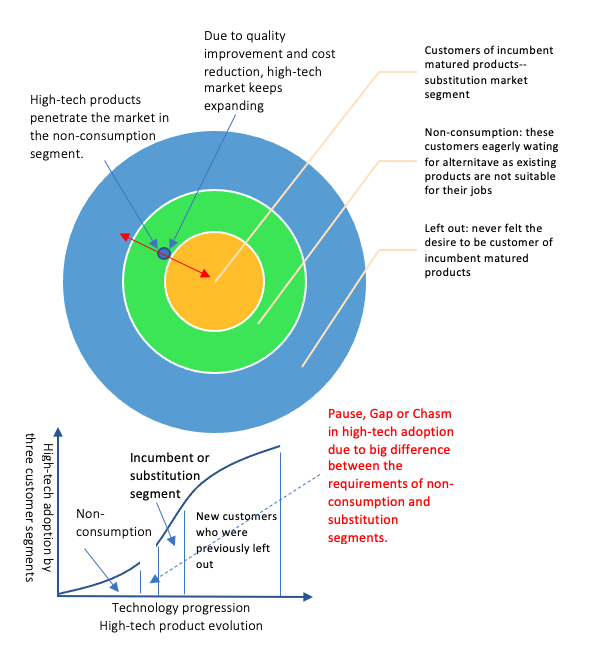

- high-tech market segments—as opposed to Rogers’ five segments, this article proposes three segments of high-tech innovations: (i) Non-consumption, (ii) Substitution, and (iii) Left out (looking for a better name).

- discontinuity in high-tech innovation diffusion—as technology risks facing hurdles at any stage of progression, chasms, pauses, or discontinuity may occur anytime, and multiple times, in high-tech innovation diffusion.

To draw lessons from examples of high-tech products

- Personal computer (PC)—in the late 1970s, personal computer started as a primitive alternative to mini and mainframe computers. The initial market was among the hobbyists. However, due to the advancement of microprocessors and memory technology core, personal computers started performing better and being less costly. As a result, companies and individuals who had never used mini and mainframe computers began buying them to perform serious work such as document preparation, as replacement of typewriters. On the other hand, corporations started replacing mini and mainframe computers with networked PCs (client-server architecture).

- Digital camera—the invention of the electronic image sensor technology core led to the development of the digital camera. In the late 1970s, it emerged as a primitive device. However, due to its unique characteristics of capturing images as digital data, customers who could not meet their requirements with film cameras started adopting primitive alternatives. Notably, the early digital camera market was the space-born imaging platform, real-time industrial inspection, and tracking of flying objects like missiles and fighter jets. Due to further enhancements in quality and cost, digital cameras became a better alternative to film cameras. Further advancement and integration in mobile phones made everybody a customer of digital cameras.

- Word processor—in the 1970s, the word processor emerged as a primitive and expensive machine. However, due to its unique characteristics of ease of editing and storing, large corporations and legal firms, among others, started adopting them. Subsequently, due to the rapid advancement of PCs, word processors became a solid substitute for typewriters.

- LCD—the most significant liquid crystal display market (LCD) is now smartphones, computers and televisions. However, in the early 1980s, it started the journey as a primitive display—a seven-segment display. The initial market was watches and calculators, as they could not use mainstream display cathode ray tubes. Further advancement led to its penetration in the mobile handset market. Subsequent advancements made it suitable to replace CRT in the mainstream market.

- Autonomous vehicles—due to primitive emergence, autonomous cars cannot penetrate the mainstream market. However, due to its unique characteristic of driving without humans onboard, the military has started adopting this primitive emergence. Besides, automobile makers are targeting elderly people as customers of it at this early stage, as it relieves elderly people from active driving.

Characteristics of high-tech products

- Reinvention—invariably, high-tech products are reinvention versions of existing matured products. For example, LCD is a reinvention of CRT displays. Similarly, a word processor is a reinvention of typewriters.

- Unique ability—reinvented versions of existing products due to the replacement of matured technology core high-tech ones have unique attributes. For example, a digital camera captures images as electronic data instead of exposure on film. Similarly, the word processor offers easy editing. And mobile phones are not tethered.

- Primitive emergence—irrespective of the greatness, invariably, all high-tech products have emerged in a primitive form as a reinvention of matured products. For example, in the 1980s, LCDs and PCs were primitive, far inferior alternatives to CRT and minicomputers, respectively.

- The rapid growth of technology core—the underlying technology cores of high-tech substitutions of matured products are highly amenable to progression. For example, microprocessors and the memory of PCs started rapidly growing. Similarly, the resolution of the image sensor went through exponential growth.

- Increasing quality and decreasing cost—unlike conventional mechanical, electrical, and electromechanical technology cores, high-technology cores, mainly in the form of semiconductors, software, connectivity, standards, and platforms, are amenable to getting better and cheaper simultaneously. It has been happening due to Moore’s law in semiconductors, zero cost of copying of software, positive externality effects of connectivity and compatibility, and scope effect of platform.

Conventional market segmentation—being applied in high-tech?

Dr. Rogers segmented adopters of hybrid seeds and other agricultural innovations into five groups based on psychographic characteristics and risk management ability. Hence, according to Dr. Rogers’ study in agricultural innovation diffusion, there are five market segments: (i) innovators, (ii) early adopters, (iii) early majority, (iv) late majority, and (v) laggards. He laid out such findings of market segmentation of innovation in his book “Diffusion of Innovation.”

Subsequently, while working in Silicon Valley high-tech marketing firm Regis McKenna, Inc., high-tech marketing experts like Warren Schirtzinger and Geoffrey Moore kept using Rogers’ market segmentation as a reference model for high-tech marketing. Besides, the Diffusion Research Institute has been promoting Rogers’ market segmentation and diffusion model. However, Rogers, in his 2003 speech on innovation diffusion, shared on the Diffusion Institute website, hinted at the limitation of his model in explaining the reinvention issue, which is a critical element of high-tech innovation.

High-tech market segments

As explained, high-tech products are invariably reinventions of existing mature ones. They emerged as primitive alternatives. However, in addition to unique attributes, they are amenable to progression, making them increasingly suitable and less costly for Getting jobs done. Hence, based on such characteristics, high-tech markets are broadly segmented into three segments:

- Non-consumption–a group of customers who strongly desires to adopt existing mature products but cannot do it due to high cost or inappropriateness. For example, despite the urgency, film cameras were unsuitable for real-time tracking objects like missiles or fighter jets. Hobbyists also fall in this category. For example, despite intense desire, in the 1970s, young stars could not instantly take pictures, take a look at them, and erase them with film cameras. Similarly, high school students could not play with computers in the 1970s. Invariably, the primitive emergence of high-tech innovation begins the journey through penetration in this segment.

- Substitution—customers in this segment have already adopted incumbent matured products. High-tech innovations must grow in quality to make them suitable for these customers to replace the already adopted matured products. Hence, there has been a time delay for this segment to adopt high-tech innovation.

- Left out—they are neither users of existing products nor desperately waiting for similar products. They called left out—looking for a suitable name. For example, in the 1980s, farmers in Bangladesh and many other less-developed countries did not think of adopting telephones, cameras, or portable storage. However, the continued progression of high-tech reinventions of telephone (mobile phones) has made them suitable for adoption by this segment.

Inappropriateness of Rogers’ segmentation for high-tech market

Does it mean Rogers’ psychographic characteristics-based model is irrelevant to high-tech market segmentation? Of course, it has relevance. However, uniqueness and economics play a far more critical role in the adoption of high-tech innovation.

Unlike hybrid seed, high-tech innovations do not create the same economic benefit for all customers. Besides, high-tech innovations are not static like hybrid seeds. Instead, high-tech innovations keep progressing, increasing the quality and reducing the cost. Hence, instead of psychographic characteristics, changing economic value and cost keep expanding the market of high-tech innovations. However, within the same group at a particular state of maturity, due to psychographic characteristics, not all the customers adopt high-tech innovation simultaneously, resulting in a time lag in adoption.

Nature of adoption growth of high-tech innovations

As high-tech innovation diffusion through different market segments depends on the uniqueness of Jobs to be done and economics, high-tech innovation diffusion is a time function. However, two major reasons exist for creating pause or discontinuity in the diffusion function. The first one takes place between non-consumption and substitution market segments. It happens because high-tech innovations must progress to make them suitable for substitutions. It resembles a chasm between early adopters and the early majority, as mentioned by Geoffrey Moore. However, Geoffrey Moore’s finding is based on Rogers’ model, which this article finds to be inappropriate for high-tech innovation.

The second source of chasm has been due to an ongoing uncertainty in technology progress in addressing the quality and cost issues. Technology may pause anytime, creating a discontinuity in diffusion progression. Hence, high-tech innovation function or the progress through different market segments naturally tends to suffer from discontinuity—creating a series of micro chasms.

Summing up

it appears there has been a severe mismatch between the underlying reasons for time-delayed responses of different customer groups to hybrid seed and high-tech innovations. Despite such a reality, the Rogers model still dominates high-tech market segmentation. As a result, innovators suffer the risk of lack of clarity and confusion in the endeavor of detecting customers at different stages of maturity of high-tech innovations. Hence, upon the consideration of characteristics of high-tech innovations and underlying reasons for time-varying adoption responses, this article has proposed a new segmentation scheme comprising three segments: (i) Non-consumption, (ii) Substitution and (iii) Left out (looking for a better name).

In addition to clearing confusion and offering better clarity, we hope this article will encourage further research in investigating practical examples of high-tech diffusion—resulting in further clarity in high-tech market segmentation and diffusion function.

3 comments

Many of the world’s most influential thinkers on business and technology-adoption [including Tom Peters and Theodore Levitt] have published studies that show this article is 100% incorrect. Anyone interested in learning from a true master of business innovation should start by reading the article “The Eye of the Beholder,” which you can find here: https://www.hightechstrategies.com/eye-of-the-beholder-and-product-perception/

Thanks for your observation that there has been a substantial difference between already published theories and this article in abstracting how high-tech innovations diffuse. Exactly for this reason, we felt compelled to write about it. As we know, theories have been evolving to increase the accuracy of abstracting the unfolding reality. To draw further insights, let’s try to comprehend how high-tech innovations like transistor radio, digital camera, personal computer, and mobile phone have evolved and diffused through different segments. Let’s attempt to figure out how far the theories you referred to and this article clarify the unfolding diffusion patterns of those innovations.

Interesting post! I completely agree that segmenting the high-tech market is crucial for businesses to identify and target their ideal customers. The waves approach provides a practical framework for segmentation, and I appreciate the examples provided. As a reader, I was wondering if you could expand on the ‘innovators’ wave? How do businesses identify and reach out to these early adopters, and what are some strategies for engaging with them?