R&D outputs have been growing. There has been very high growth in publications, patents, and STEM graduates. Particularly, outputs from China, India, and many less developed countries are showing an exponential growth trend. Nevertheless, why should we entertain a proposition that the endless frontier has been weakening? But, upon the investment of more than $80 billion in autonomous vehicle R&D, innovators are yet to see revenue flowing. There have been many such examples, from ride-sharing to AI-based disease diagnosis Startups. Despite the skyrocketing publications, patents, and availability of risk capital, why are ideas failing to reach the market at a profit? Does it mean that Innovation has been facing a growing barrier in creating Wealth? Does it mean that as opposed to a great idea, we need a Flow of Ideas? And that the demand for a flow has been expanding.

Research investment is for the purpose of digging out ideas to fuel economic growth burner. But it appears that like physical mines, idea mines are also getting deeper. Hence, research needs increasing investment to get valuable ideas to fuel growth. Therefore, innovators face the reality of spending increasing R&D efforts to find fewer profit-making ideas. As a result, growth prospect out of innovation has been slowing down in both advanced and developing countries. Such reality is raising the question of whether the endless frontier has been weakening. If it does, the human race will likely face a bleak future, with the agenda of creating increasing wealth. Hence, it’s imperative to find the likely solution for arresting the rapid decline of R&D productivity.

Low hanging fruits are already picked up:

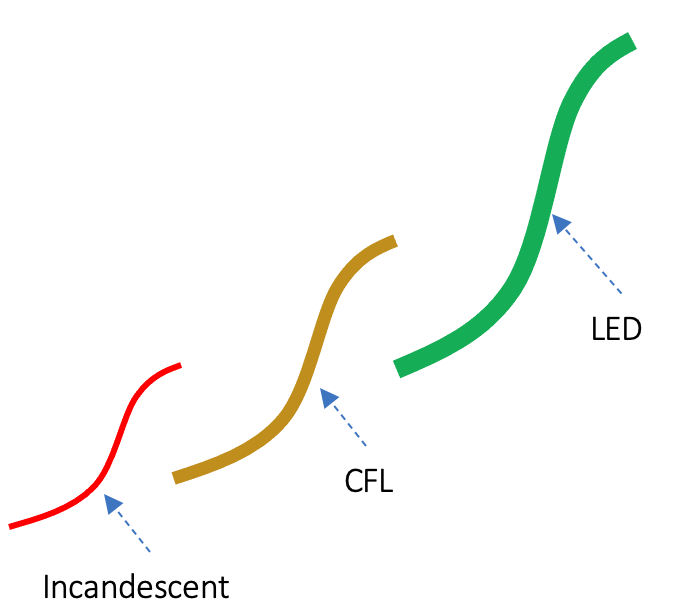

With the savings from his wife’s salary, Carl Benz financed the R&D in securing the first patent for inventing the automobile in 1879. Although it emerged as a tricycle, that primitive emergence did not take much effort and time to get a car’s shape for profitable revenue. Similarly, with the idea of producing light by heating filament with electricity–Mr. Edison started the electric lighting business. Yes, Edison needed an additional flow of ideas to refine for expanding the diffusion. Hence, he set up an R&D lab in 1899. But it did not cost millions of dollars over a decade for starting the profitable revenue. But the Reinvention of Edison’s bulb through changing the filament with LED chip demanded 30 years-long research, ending up with Nobel Prize-winning scientific discovery.

Similarly, the idea of reinvention of Carl Benz’s automobile by Tesla, turning it into an electric vehicle, has been burning billions of dollar investors’ money over almost 20 years. Another idea of automobile reinvention, turning it into an autonomous vehicle, has already gobbled up $80 billion in R&D investment. But there is no sign of the immediate release of such cars on the street. It seems that low-hanging fruits in the innovation orchard have already been picked up.

Burning issues

The exponential growth in R&D to find and nurture profitable ideas is slowing down economic growth out of innovation. As a result, advanced countries have been losing confidence in R&D in driving economic growth. Hence, some of them, including the USA, have shown growing signs of embracing isolationism to protect their industrial economy. For less developed countries, protectionism does not do much. With the exponentially growing R&D investment need for having economic growth out of innovation, what is the option left for them? What is left for further development to avoid the middle-income growth trap after exhausting natural resources and labor?

Growing innovation barrier: Is endless frontier coming to an end?

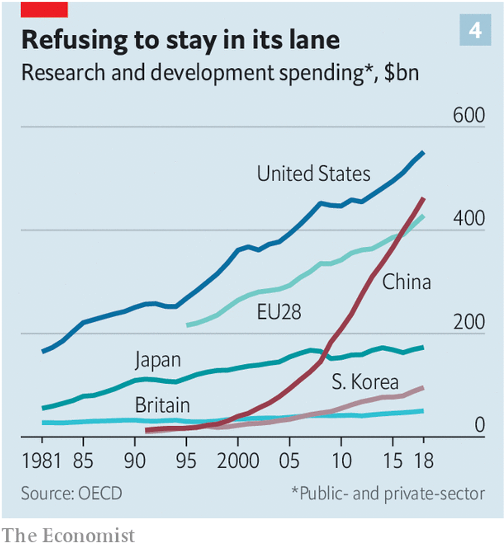

Given data indicates that exponentially R&D investment is needed for fine-tuning big ideas. It’s is getting increasingly harder to find the needed flow. Hence, advanced economies like the USA have been exponentially increasing research funding to maintain the growth rate. Does it mean that growing investment for offsetting declining R&D productivity is narrowing down the opportunity of endless frontier of growth out of science, technology, ideas, and innovation?

More or less, there has been a consensus among the intellects and policymakers that R&D investment has a strong positive correlation with economic growth. Hence, every country has been increasing its R&D budget. But not long ago, we did not have this belief. For example, Edison’s R&D lab, established in 1899, was the first attempt of corporate America to leverage systematic research to expand revenue and profit. Similarly, before WWII, the US government did not have a noticeable R&D fund for exploiting science to drive economic growth. The demonstration of the role of science and technology in winning the war created confidence in the US administration.

Subsequently, Dr. Vannevar Bush’s report–science the endless frontier– led to US policies exploiting the endless frontier of science for driving economic growth. Hence, the public-funded National Science Foundation, ARPA/DARPA, and other institutions started popping up, forming the USA’s national innovation system. The flow of knowledge and ideas created by these programs also started fueling the private initiatives of innovation and entrepreneurship. Subsequently, the European countries and other industrial economies followed this model. Due to early demonstration of correlation between indicators like STEM graduates, publications, patents, and economic growth, development pundits have been prescribing this model to less developed ones to follow. But deepening innovation mine has been raising the question of further scalability of this model.

Research produces economic gain:

Often, measuring research productivity runs into a debate. Notable, researchers and academics are counting graduate degrees, publications, and patents. But from the economic growth perspective, unless those outputs result in innovating new products or improving existing ones, they have no role in creating wealth. Hence, for the purpose of driving economic growth out of research, productivity refers to the ratio between R&D investment and additional revenue that distills from the integration of research outputs. They must improve products and processes for increasing consumer and producer surpluses. Hence, until intellectual assets, delivered by research, are integrated to improve the quality and reduce the cost of products, it produces no economic value. Despite the rapid growth of R&D outputs, research finds a weakening correlation between them and economic growth. Hence, researchers from Stanford University have been referring to deteriorating R&D productivity.

Increasingly taking deeper work to innovate: weakening endless frontier

We have a strong belief that innovation is the creative spark of a solo genius. But that is not the case in most cases. Invariably, all great ideas emerge in primitive form. They need a systematic flow of ideas for creating economic value. Even Edison’s invention alone did not create much economic value. It needed a systematic flow of ideas to form an R&D effort to create the value we know of. Similarly, Steve Jobs alone could not show any of the innovation magic. Dozens and thousands of people have been systematically doing R&D in producing and rolling out ideas to extract economic value. Besides, in addition to Apple, more than 200 suppliers have been advancing each of the components to enable iPhone to generate increasing revenue and profit. Apple and its partners invest billions in R&D for releasing the next version.

The basic economic concept is simple– increasing funding for research will enable researchers to keep coming up with growing ideas; consequentially, we will be experiencing more economic growth. Quite contrary to such common belief, researchers disappointedly find that while research efforts are rising substantially, research productivity—commercially attractive ideas being produced per researcher—is declining sharply.

Declining research productivity: increasing the number of researchers is the offsetting strategy

There has been no denying that each unit of R&D investment has been producing a decreasing amount of economic value. Furthermore, the declining trend has been exponential. To offset it, the USA has been after a steep increase in research and development funding so that it can offset the erosion in research productivity. Due to it, exponential growth in R&D funding has been the strategic reality for the USA to maintain the economic growth rate. Hence, the number of Americans engaged in R&D has jumped by more than twentyfold since 1930. Such a sharp increase has been to offset the collective productivity drop by a factor of 41. These numbers indicate that engaging a growing number of R&D personnel is the survival strategy to roughly maintain growth, as creating economically attractive new ideas out of research is getting harder.

Let’s get further clarity from the semiconductor industry. We are all happy with doubling the Silicon chip density every 18 months. But that output has been due to the growth of research effort behind chip innovations by a factor of 78 over 70 years, since 1971. Hence, for maintaining the same level of innovation in semiconductors, we need 75 times greater R&D effort than that we needed in the early 1970s. Like microelectronics, other sectors are also showing similar R&D productivity decline. For example, for maintaining steady growth in agricultural yield during 1960–2015, the research expenditure has gone up as high as more than 25-fold.

The growing innovation barrier is creating an inescapable middle-income trap:

Among others, Stanford’s reported research findings conclude with alarming observations. Based on economic contribution, over the last 30 years, R&D productivity has been falling, on average, about 10 percent per year. Hence, we require 15 times more researchers today than we did 30 years ago to produce the same rate of economic growth. Such sharp declining R&D productivity has been a cause of concern for both advanced and less developed economies. For sure, middle-income countries will not likely find R&D investment as the way out of the middle-income trap.

Growing maturity and increasing reinvention barrier are weakening endless frontier:

For sure, growing research outputs are indicating the expansion of our knowledge base, idea portfolio, and the STEM workforce. But why are not making a proportionate contribution to economic growth should be investigated further. First of all, most of the R&D efforts are for the purpose of incremental improvement of existing products and processes. In most cases, the technology cores of them have them reach near saturation. Hence, the marginal productivity of ideas has slowed down. On the other hand, the gap between the beginning of the reinvention wave and the inflection point has been getting larger. As a result, increasing R&D outputs have been failing to make proportionate economic value creation.

Perhaps, there is no easy way out. One of the options has been to pay attention to reoccurring patterns of innovation dynamics so that errors in decisions are reduced for lowering wasteful investment Indicators like 97 percent patents do not contribute to economic, as high as 90 percent of startups fold up within three years, and more than 80 percent innovations retire without producing profitable revenue refer to high wasteful R&D outputs. Therefore, we should pay focus on studying Market Dynamics in shaping ideas into wealth or waste for increasing R&D productivity. Perhaps, finding a way of improving decision-making will lead to addressing weakening endless frontier issues.

...welcome to join us. We are on a mission to develop an enlightened community by sharing the insights of wealth creation out of technology possibilities as reoccuring patters. If you like the article, you may encourage us by sharing it through social media to enlighten others.