We all are after economic growth for getting rid of scarcity. But, limited natural resources cannot offer endless growth. Hence, we have been after Innovation for exploiting ideas to derive increasing economic value from limited resources. But how to guide our decision making to distill economic value from ideas. Therefore, economists have delivered several economic growth theories, such as the Solow growth model and endogenous growth theory. These are attempts to correlate ideas, human capital, labor, and physical capital in producing economic value. Despite all the help we get from those theories, policymakers are clueless about how to drive economic growth out of innovation predictably. Economists have been struggling to suggest policy instruments to replicate the success of Japan or Taiwan for other less developed countries. On the other hand, firms and governments alike have been failing to sustain economic prosperity out of inventions and innovations.

Creating economic value from ideas is human beings’ inherent ability. Long ago, philosophers repeatedly made this observation, as noticed by Carl Marx. For this reason, over the last 2000 years, both per capita GDP and population have been growing simultaneously. The Market Economy adopted the principles for intensifying profit-making competition to tap into this capability. Some of those principles are ownership of capital, exclusive rights of exploiting economic value from ideas of invention and innovation, and freedom of competition to profit from better ideas. But as high as 97 percent of patented ideas fail to create any economic value.

On the other hand, economic success migrates across the boundaries of firms, industries, and countries. Furthermore, how to produce and leverage ideas through optimum resource allocation is also an issue. Hence, economists have been after theories to help us develop appropriate policy instruments. But their roles in policy formation to tap into growth are questionable.

Cobb-Douglass production function–starting of economic growth theory

From 1927 to 1947, Charles Cobb and Paul Douglas performed statistical analysis on the production of economic outputs, giving birth to the Cobb–Douglas production function. It represents the economic outputs as a function of two or more inputs, such as physical capital and labor. In the simplest form, it’s described as Y=ALαKβ; L and K stand for labor and capital. The value of coefficients (α and β) are the output elasticities, and they are constant for the given available technologies. ‘A’ represents total factor productivity (TFP), the portion of the growth in output not explained by growth in inputs of labor and capital used in production. Often, we refer to TFP as the contribution of knowledge and ideas. Hence, for leveraging growth beyond labor and capital, economists are after TFP.

Despite the importance of TFP, it seems that Cobb–Douglas production function could not explain how it contributes to economic value creation. Hence, they looked into it as an exogenous factor, somehow related. Due to its likely linkage with knowledge and ideas, economists kept suggesting increasing investment in education and research.

Solow Residual for articulating economic growth:

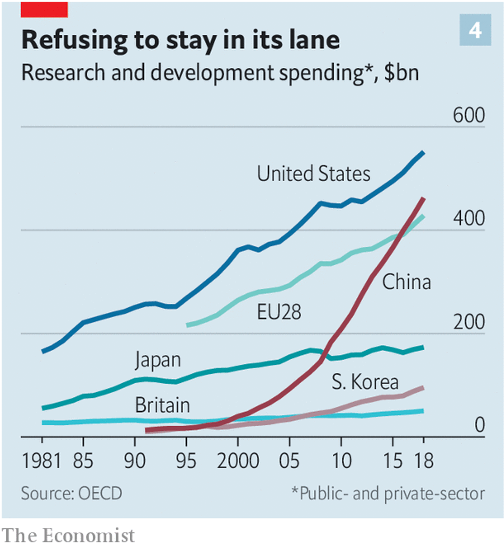

In the 1960s, Prof. Robert Solow analyzed economic data and came up with the observation of a portion of economic growth not contributed by the labor and capital supply growth. He termed it Solow residual. He also opined that it came from the growing expansion of science and engineering education and investment in R&D. Hence, economic growth theories gave further emphasis on higher education and R&D got another boost. Notably, he argued that due to the sudden rise of public funds for R&D during the 1950s and 1960s, the economy of the USA experienced high growth.

Human capital theory:

During the 1970s and 1980s, notable economists worked on the concept of human capital. This is about the role of knowledge, ideas, and labor, which human beings provide to create economic value. They argued that by providing education and investing in research, we could upgrade the human resource to human capital. Therefore, they brought a new role of the human in the production of economic outputs, Y=f(K, L, H); H stands for human capital. Therefore, investment in education got further importance. Subsequently, some development institutions and Think Tanks started ranking countries with respect to human capital. It created the impression that better human capital higher economic growth. Hence, it has contributed to policy decisions in favor of increasing investment in education and research. Notably, there has been an exponential growth in the production of university graduates, publications, and patents.

For example, in recent times, India’s growth rate of scientific publication was 12.9 percent, as against the world average of 4.9 percent. India showed far higher performance than China and the United States’ average annual publication growth rate, 7.81 and 0.71 percent respectively. For example, between 2008 and 2018, with 10.73 percent, India recorded the fastest average annual growth rate of publications. Many other less developed countries have also experienced similar growth. There has been similar growth in enrollment in higher education in less developed countries. For example, according to a recent Brookings India report released in November 2019, enrolment in India’s 52,000 higher education institutions in 2019 was four times what it was in 2001.

Endogenous growth theory:

To bring further clarity about the role of ideas in creating economic value, Prof. Paul Romer has introduced endogenous economic growth theory. He has articulated economic output as a function of ideas and objects—Y=f(A, X); A stands for ideas, and X refers to objects. This theory creates a tendency to believe that investment in increasing the supply of ideas will lead to higher economic growth. Furthermore, the correlation between the volume of patent portfolios and the economic growth of a few countries supports this theorization. Hence, this endogenous growth theory tends to encourage increasing R&D investments for creating the supply of ideas. Consequentially, there could be a race among less developed countries in increasing the value of relevant indicators such as publications and patents. For example, China has experienced exponential growth in R&D funding, publications, and patents. But does it lead to proportionate economic growth?

Trend and statistics of failure:

Although all the economic growth theories are in favor of advancing education and publications for increasing the role of human capital, many less developed countries, including India, have been experiencing growing unemployment among graduates. For example, more than 80 percent of engineering graduates in India do not find engineering-related jobs. Similarly, in Bangladesh, as high as 50 percent of university graduates are unemployed. Besides, as high as 97 percent of patents find no commercial use on the patent front. Furthermore, despite the rapid growth of publications, countries like India, Malaysia, and China have not shown any sign of distilling proportionate economic value from them. Furthermore, different studies have found that as high as 80 percent of innovative products released in the market have been failing to produce profitable revenue.

Therefore, in hindsight, there appears to be a very weak correlation between human capital advancement, idea supply, and economic growth, notably in less developed countries.

Role of understanding of dynamics and decisions:

Knowledge, ideas, and human capital do not create economic value in isolation. Hence, production and possession of them alone is not a sufficient condition. Actors must win the competitive race in a globally connected market to create opportunities. For example, the same unemployed STEM graduates in Bangladesh find a suitable job in Japan to create economic value from their knowledge. Similarly, all the firms and countries do not equally succeed in turning access to the same patents into profitable revenue. Furthermore, the economic value of an idea is dynamic due to the formation and growth of substitutes as Creative waves of destruction. Besides, the scope of creating economic value from knowledge and ideas in production has been falling due to increasing automation.

It appears that the competitive dynamics have been turning knowledge and ideas into Wealth or waste. In retrospect, the possibility of turning ideas into waste is relatively high, as high as 80 percent. Furthermore, the growing monopolization of technology possibilities leaves little or no room for followers. Hence, although the opportunity to get an education and advance knowledge is quite addressable, the scope of creating economic value is determined by the dynamics of technology and innovation in the competitive market. Due to this reality, many companies and countries have been failing to turn their human capital, patents, and physical capital into economic value.

Updating economic growth theories:

The underlying problem has been in decision-making and strategy formulation. Therefore, in the absence of an understanding of technology innovation dynamics in a globally competitive market, there is a high risk of failure in pursuing economic growth theories. Hence, the economic theory could be reformulated as Y=f(K,L,H,A,D). Here, D refers to the understanding of dynamics and taking decisions accordingly. There should be a strong alignment between D, A, H, L, and K for leveraging the investment we make.

...welcome to join us. We are on a mission to develop an enlightened community by sharing the insights of wealth creation out of technology possibilities as reoccuring patters. If you like the article, you may encourage us by sharing it through social media to enlighten others.