For encouraging local ideas and increasing the affordability of industrial products, India has been promoting frugal Innovation and jugaad. Despite promises, these two approaches do not offer a scalable path for driving economic prosperity, and quality of living standards. Instead, they run the risk of misguiding development thinking, creating confusion, and wasting time.

India has become the land of frugal innovation and jugaad. Frugal innovation or frugal engineering is the process of removing non-essential features from a durable good. In systematic inventive thinking, this is the application of the subtraction tool. There is another word referring to a similar concept. This is ‘Jugaad’. The Hindi word ‘Jugaad’ is a way of life in India. It describes an improvised or makeshift solution using scarce resources. For example, jugaad refers to using discarded plastic bottles to make flower pots. On the other hand, frugal innovation targets developing strip-down versions of existing industrial products like cars or mobile phones to make them affordable in performing essential tasks.

Although these two approaches look into the problem from two different perspectives, both aim to offer less costly solutions to get jobs done. At the dawn of the 21st century, there has been a strong interest in frugal innovation and jugged in India. Do they offer a new development too to India? Or, is it the fact that frugal innovation and jugaad are promoting something that has no future to scale up?

Progression of innovation in perspective

Human beings have the urgency to come up with ideas to reorganize things to get jobs done better. This is tinkering approach-based innovation. For example, in the absence of an umbrella, we can place a plastic bag on the head to prevent from getting wet. Of course, this is innovation. But why does it not scale up as a substitution to the umbrella? If we review human history, we will observe numerous examples of Jugaad. However, those tinkering-based innovations are losing ground. Modern industrial products are taking over their places. People are finding that industrial products are far better alternatives to Jugaad. That is the reason people buy an umbrella, instead of using large plant leaves or plastic bags during rain.

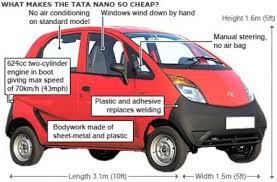

Let’s now look into frugal innovation. The core thesis is to subtract non-essential elements and produce a simpler version. This strip-down version will perform the essential tasks but at an affordable price. Tata nano is a prime example. Let’s look into the invention and evolution of the automobile. In fact, it emerged as frugal innovation. Initial emergence had only essential components. However, innovators kept improving it by adding one after another feature and also improving existing ones. In certain cases, the cost increased. But customers did prefer to pay even more for the successive better versions, as long as the marginal Utility has been far greater than the marginal cost.

Examples of getting better and cheaper

However, for certain products, the cost has come down. For example, a microwave oven or TV costs now far less than in the 1950s. Similarly, once inflation is taken into consideration, even a typical family Sedan costs less than the Model T of Ford. The price of Model T in 1908 was $825—equivalent to almost $23,000 in today’s value. The actual price of a Microwave oven in 1947 was hopping $5000. Similarly, in the 1950s, RCA priced the popular model of its Television at $435.

India’s self-dependence—is there a lesson for Frugal Innovation and Jugaad?

After the independence in 1947, India attempted to make every industrial product they used by themselves. Hence, they adopted the policy of importing capital machinery and taking foreign products’ licenses for local production. However, for many products, they condoned the infringement of intellectual property rights. They also imposed high import restrictions on those products which India started producing locally. Within a few years, India began witnessing the rollout of many products, including automobiles, from their local plants. It gave the impression that India made rapid progress in developing a prosperous industrial economy. Hence, some people got the impression that India was on the path of becoming an industrially prosperous, developed country shortly.

However, within a couple of decades, India started seeing in deep economic crisis. Indians kept using the same locally produced Morris Oxford series II, which did not change over 30 years. During this period, neither the product nor the process did experience any redesign—with the support of local ideas–to improve the quality and reduce the cost. On the other hand, the Japanese started offering increasingly better cars, at decreasing cost. Not only automobiles, but most of the locally produced industrial products also faced the same fate. India’s local production’s initial successes failed to sustain because India could not make needed progress to keep producing and adding intellectual assets in making those products incrementally better and cheaper. Hence, India got stuck and was compelled to liberalize imports.

Frugal innovation and jugaad—is it a new initiative to keep India on a slow lane?

Both frugal innovation and jugaad sound encouraging, highly nationalistic. It also sounds more humane. Let’s look into the basic purpose of frugal innovation and jugged. The frugal innovation targets to offer affordable versions. In fact, affordability is at the cost of removing features. However, those non-essential features produce utility. They contribute to the quality of living standards. For example, Tata Nano is affordable to the low-middle-income group. To make it affordable, Tata removed many features, including the air conditioner. Those feature removals reduced the utility so much that target customers rejected the affordable Tata Nano.

How can we reduce the cost of cars, refrigerators, or phones for increasing their affordability without removing features? Fortunately, there are alternatives. Let’s look into the microwave oven. At birth, this $5000 product was not affordable to American households. To address this issue, the Japanese embarked on R&D for technological breakthroughs for offering Microwave Oven at $500, 10 times cheaper. And it was far better than the original one. As opposed to removing features for reducing cost, the Japanese added intellectual assets. Similarly, let’s look into the price of the mobile phone handset. Motorola’s DynaTAC 8000X, costing $3995, did not have many features that a $100 phone set has now. What is the secret recipe for offering additional features at a lower cost?

Similarly, 500 years ago, most of the products our ancestors used were Jugaad. The transfer of Jugaad to science and technology-based scaleable path of progression is the underlying cause of sustained growth of the economy and our quality of living standards. Is it a wise decision to go back 500 years to learn that it’s not a smart approach?

Time to go back to basics

The fundamental purpose of frugal innovation and jugaad has been to leverage people’s creativity and make state-of-the-art industrial products cheaper. Exactly, that has been the underlying driver of the modern industrial economy. The competition has been to offer increasingly better-quality tools to customers at a lower cost. In doing so, as opposed to removing features, they are adding features. For addressing the conflicting relation of higher quality at a lower cost, they are adding technology ideas. Those ideas out of scientific discoveries and technological inventions are reducing the need for materials, energy, and other tangible inputs. The smarter option for India and other developing countries should be to scale up the progress of adding locally produced ideas to the products and also to processes to produce them, to make them increasingly better and cheaper.