The light bulb is a metaphor for invention and Innovation. Often, we think that a creative spark in the mind of genius leads to a great invention, leading to innovations of usable products. In contrary to common belief, invention emerges as the outcome of a series of creative sparks, produced by multiple genii. Moreover, initial emergence frequently manifests in a very primitive form. This primitive technology shows the potential of innovating useful means to get our jobs done better. Early versions are far from usable and affordable to consumers and profitable to the producers. Nonetheless, the demonstrated idea starts beckoning profit-making opportunities through the refinement of invented technology and innovating successive better versions of usable products. The history of the light bulb is no exception. The invention and evolution of the light bulb are not credited to a single creative spark of a Genius like Thomas Alva Edison.

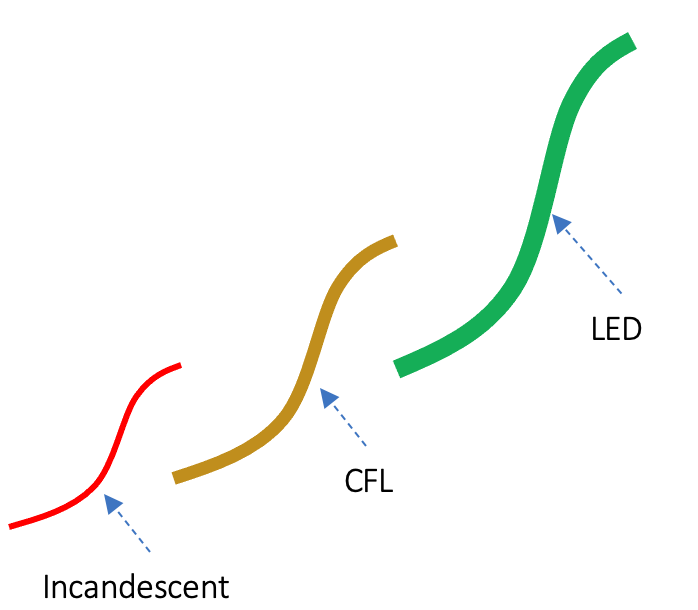

Furthermore, the light bulb has been evolving, transforming jobs and industries. The evolution of the light bulb also offers us reoccurring patterns in interpreting, predicting, and strategizing the industrial economy. The evolution path of light bulb innovation is also littered with unfolding Creative waves of destruction. Most importantly, the evolution of the light bulb is at the core of its progressive diffusion as growing waves.

Key takeaways of light bulb invention and innovation

- Inventor and invention date of the light bulb— No single individual invented the light bulb from a sudden spark on a certain date. For the invention of the incandescent light bulb, Thomas Alva Edison received a patent in 1879. However, William Edward Sawyer and Albon Man deserve significant credit for the invention of the incandescent light bulb. Besides, during the early part of the 19th century, British scientists experimented with producing light from electricity, resulting in light production through an electric arc.

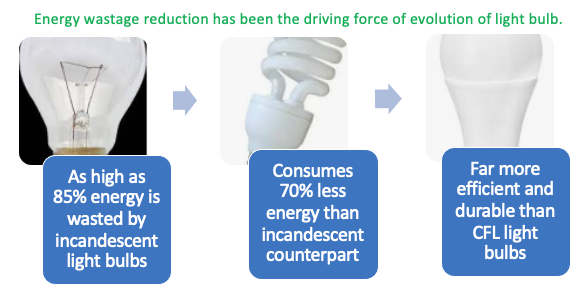

- Evolution of the light bulb–Since the invention and beginning of commercialization, the light bulb has been evolving. To reduce the wastage of energy, increase the life span, and improve the quality of light, the light bulb has been evolving over 140 years through incremental advancement and change in light producing technology core–leading to highly energy-efficient LED light bulb.

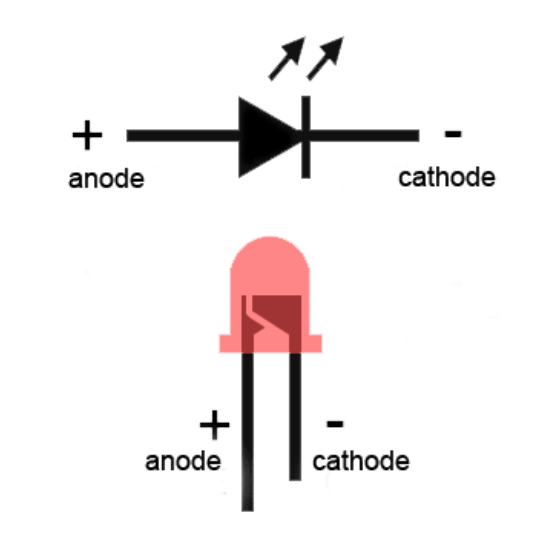

- LED light bulb invention–LED light bulb invention is the culmination of the efforts of many scientists. Nick Holonyak is considered the father of the LED light bulb due to his invention of the first LED that produced visible, red light while working at General Electric, in 1962. However, his invention was not sufficient enough for the LED light bulb we use for lighting. To address the last scientific hurdle for making LED light bulb a feasible energy-efficient alternative to incandescent and CFL light bulb, Shuji Nakamura, Isamu Akasaki, and Hiroshi Amano made a scientific Breakthrough–making a perfect blue LED–in 1994 for which they received a Nobel prize in Physics in 2014.

Invention and evolution of the light bulb–who should be credited for?

Thomas Alva Edison was awarded a US patent for the light bulb in 1879. However, long before it, many creative minds contributed to the idea of the light bulb. In the early 19th century, British scientists experimented with the idea of producing light from electricity through an electric arc. It led to the demonstration of the first constant electric light from arc lamps in 1835. However, that demonstration did not lead to commercialization. Over the next 40 years, the journey was finding alternative technology core for producing better quality light at less cost. Candidate technology was filament for developing an incandescent lamp to replace the arc lamp. Tinkering kept progressing to produce light by heating filament by passing through electric current.

However, like many other inventions, early incandescent bulbs had extremely short lifespans. They were too expensive to produce, and they used too much energy. Consequently, neither consumers saw much Utility in it, nor did producers find profitable business opportunities. Nevertheless, it planted the seed of a long journey of the evolution of the electric light bulb.

Long after 50 years of arc lamp demonstration, Edison and his researchers at Menlo Park in the USA came onto the lighting scene. As opposed to inventing a new technology core, they focused on improving the filament of the incandescent lamp. Edison’s tinkering led to producing a light bulb with a carbonized filament of uncoated cotton thread that could last for 14.5 hours by October 1879. Even upon getting the patent, Edison did not stop there. His continued refinement for finding better filament, leading to bamboo. Of course, we should also mention the names of William Sawyer and Albon Man, who received a patent for the incandescent lamp from US and UK patent offices respectively.

Evolution of light bulb through Incremental innovation

The idea of the light bulb opened profit-making business opportunities led to the formation of GE-General Electric. On the one hand, Edison’s company GE focused on developing the electric power production and distribution facility to expand the market. On the other hand, competitors started to enter. One of the notable ones was Philips from Europe. At the very early stage of the electric lighting revolution, Philips started manufacturing carbon-filament lamps in 1891. Soon after the initial success of making light bulbs, it became clear that in order to keep up with the competition, Philips needed ideas for producing increasingly reliable lamps at decreasing cost. A race of incremental innovation started, which kept evolving light bulb innovation to get better and cheaper. Furthermore, the competition has been driving, since the early days, sustaining the innovation race of the light bulb. For sure, it demands a strong capacity for idea management.

Switching to tungsten filament extended the life of incandescent lamps

In the emerging light bulb industry, GE was a forerunner. GE combined Edison’s discovery of carbon filament with complementary technology from English inventor Joseph Swan. But GE’s bulbs glowed dimly, broke easily, and lived briefly. For creating an increasing willingness to pay among the growing number of customers, GE had to improve the carbon filament. On the other hand, competitors were nipping at their heels. The initial target was to extend their average lifespan from 100 hours to more than 500. Unfortunately, the incumbent filament technology core was not amenable to growth in meeting the target. They needed to create something groundbreaking to meet the ambitious target, particularly to fend off competition.

GE and its major competitors were desperately trying to find better alternatives to carbon or bamboo filament. The list of candidate metals included Osmium, Tantalum, and Tungsten for developing hair-like thin wire which can keep glowing for more than 500 hours. Finally, the breakthrough happened in 1906 from GE’s R&D lab in New York, when a spongy rod of tungsten accidentally fell into a pool of liquid mercury from the sintering furnace. In addition to it, Irving Langmuir’s discovery in 1913 of placing an inert gas like nitrogen inside the bulb doubled its efficiency. The refinement journey continued over the next forty years, reducing the cost and increasing the incandescent bulb’s efficiency. As a matter of fact, the invention and evolution of the light bulb over almost two centuries is remarkable indeed.

Changing technology core from filament to fluorescent, leading to LED

The long refinement journey of 70 years, since the patent was issued to Edison in 1879, succeeded in converting about 10 percent of the energy the incandescent bulb used into light. On the other hand, they also found that no other combination of the periodic table they left unturned to find better filament. This observation led them to focus their energy on other lighting solutions. One of the candidate technologies was the Geissler tube, invented in the 19th century. Its light production principle is based on removing almost all of the air from a long glass tube and passing an electrical current. Some of the notable innovations around this technology core are neon lights, low-pressure sodium lamps, and fluorescent lights.

Change of technology core led to energy-saving CFL

A long journey of refinement of fluorescent lighting technology led to the innovation of compact fluorescent light (CFL). In early the 1990s, CFL bulbs were using about 75 percent less energy than incandescents, and they had a lifetime about 10 times longer. Moreover, process technology improvement led to the price fall from $25-35 in the mid-1980s to as little as $1.74 per bulb when purchased in a four-pack. Consequently, CFL emerged as creative destruction to incandescent light bulbs.

LED emerged as a far better alternative to CFL

However, the most promising technology core emerged in the 1960s. While working at GE, Nick Holonyak, Jr., invented the first visible spectrum from a light-emitting diode (LED) in 1962. LED usage a tiny amount of semiconductor (less than 1 square millimeter) to convert electricity into light. The promising journey of LED faced the barrier of producing bright blue light, which was essential for producing white light. Unlike in the past, tinkering was not sufficient to overcome this barrier. They had to dig down underlying science to detect the cause and invent efficient means to address it.

Finally, they found that the presence of hydrogen at the diode’s junction made blue light not sharp enough. Subsequently, they also developed efficient means of avoiding it. This scientific discovery, followed by the invention, led to the opening of the door of offering the better light bulb. As opposed to incandescent bulbs’ 1200 hours, and CFL’s 8000 hours, the average life of an LED lamp is 50,000 hours. On top of it, LED lighting produces light approximately 80% more efficiently than incandescent light bulbs. To recognize it, Nobel Prize was awarded to a trio of scientists in Japan and the US for the invention of blue light-emitting diodes. However, despite its radical or breakthrough nature, LED could not cause a destructive effect on the lighting industry. Of course, it powered a creative wave of destruction to CFL and incandescent lamps. Therefore, neither CFL nor LED is a disruptive technology.

The evolution of the light bulb is a collection of unfolding waves of creative destruction

Over the last 100 years, there have been three major waves of creative destruction in the lighting industry. The first one came from the emergence of GE for the commercialization of the filament light bulbs. The uprising of light bulbs destroyed lighting products like candles or oil lamps (like hurricane lamps). As opposed to candle or hurricane producers, start-ups like GE or Philips powered the emerging wave of the incandescent bulb. Consequentially, it disrupted the lighting industry based on the previous technology core. From this perspective, the emergence of electric light bulbs was Schumpeter’s creative destruction and also Christensen’s Disruptive innovation. These two effects happened simultaneously. But it does not happen all the time. For example, it did not happen to the subsequent two cases of the change of technology core. Does it mean that every megatrend does not lead to disruptive innovation?

Successive waves of creative destruction did not lead to disruptive innovation

The other two waves were created by the Geissler tube and LED technology cores. Unlike the past, as opposed to Startups, incumbent incandescent bulb-producing firms pursued those technology core. For example, GE was at the forefront in innovating, refining, and commercializing CFL bulbs. Similarly, LED was invented at GE’s lab. As a result, although CFL emerged as a creative wave of destruction to incandescent lamps, it failed to disrupt the lighting business of firms like GE or Philips who were producing light bulbs around the filament technology core. Similarly, the LED light bulb has already emerged as the next creative wave causing destruction to CFL. Nevertheless, it has failed to disrupt the lighting business of major CFL makers. In fact in the business of around $20 billion global lighting industry, still to date century-old GE and Philips are among the top ten.

Hence, creative destruction does not always cause disruptive innovation effects on incumbent firms. Such a lesson sheds light on the debate of creative destruction vs disruptive innovation.

Why did not waves of creative destruction lead to disruptive innovation?

Contrary to many other examples, incumbent firms did not suffer from Christensen’s “innovator’s Dilemma” syndrome to leverage emerging technology waves. Instead of suffering from a dilemma, whether to get in or not, they led the transformation. Hence, they avoided facing Kodak moment. Indeed, the invention and evolution of the light bulb offer a good lesson for technology and innovation management. Instead of trying to protect business around the existing technology core, which they perfected, they were desperately looking for an alternate technology core to offer better light at less cost for making money. Change of technology core creating the wave of creative destruction does not necessarily lead to disruptive innovation. It’s rather the innovator’s decision dilemma to switch to new technology core runs the risk of facing disruptive effect due to the uprising of new wave.

Despite the initial patent-holding by GE, the scope of incremental innovation gave the entry as well as a sustained profitable business opportunity to followers like Philips and Osram. On the other hand, discontinuity created by the change of technology core also opened the door for new entrants. For example, Japan’s Nichia Corporation took advantage of the emergence of LED technology core to enter the global lighting market. By the way, it’s worth noting that Nichia corporation-sponsored research for blue LED led to winning Nobel Prize by Japanese in 2014. The long journey indicates that the invention and evolution of light bulbs is not an act of creative genius like Edison.

Like the light bulb, many other great inventions like television emerged as a cumulative effect of incremental contributions made by many great creative minds. In fact, every great idea demands a Flow of Ideas to take the shape of usable products.