Prof. Clayton Christensen had a curiosity to get to know why high-performing, well-managed technology firms fail. Of course, firms will be on a declining path if they keep facing poor management practices. To his surprise, he observed that often past success plant the seed for future failure. Ironically, it’s contrary to the lesson offered by great minds like Albert Einstein: failure plants seeds for future success. He also observed that technologies play a vital role. The process of disruption starts with the emergence of a new technology core offering the possibility of providing substitutions. Subsequently, entrepreneurs start harnessing the hidden potential of offering a better alternative to incumbent products with the support of an emerging technology core. Often this journey leads to the creation of new firms while disrupting once highly performing ones. This observation led to the theory of Disruptive Innovation, commonly known as Christensen’s Disruptive Innovation and Technology.

Disruptive innovation has many connotations. Often, we use it as a buzzword. Breakthroughs or radical technology advancement are also frequently termed Disruptive technologies or innovations. However, we do not like to get lost in many interpretations of this phrase—disruptive innovation. Like Prof. Clayton Christensen, we would like to focus on the dynamic effect of the uprising of substitutions around the new technology core. Moreover, we also get confused with the phrase “creative destruction”, also known as Schumpeter’s Creative Destruction. In describing the uprising of a new wave of innovation offering better substitutions while destroying existing products, firms, jobs, and industries, Prof. Joseph Schumpeter coined that phrase in his book—Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy.

Creative destruction in the Market Economy

Disruptive innovation has a root in the basic principles followed by the market economy. Of course, some of those principles are distilled from ancient philosophical writings. Prof. Carl Marx observed a reoccurring theme in the writings of Aristotle, Socrates, and many other philosophers. They kept mentioning human beings’ inherent urge to create ideas for recreating means in getting purposes served better. This is coined as Praxis. Creators of market economy principles focused on harnessing praxis to keep driving economic prosperity. They formed principles by placing the freedom of entrepreneurship for pursuing ideas at the core. In fact, this is a core strength of the market economy for offering increasingly better products at decreasing costs. It offers profit-making incentives to entrepreneurs while increasing consumer surpluses. Consequentially, it keeps rising our living standards.

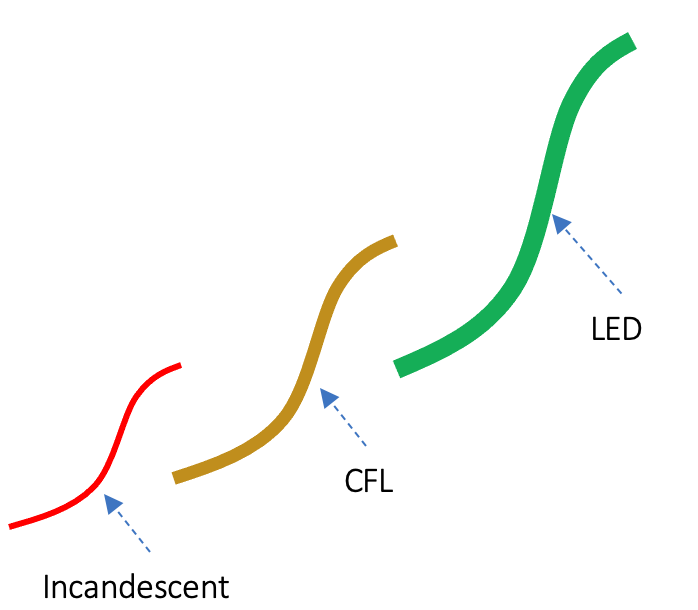

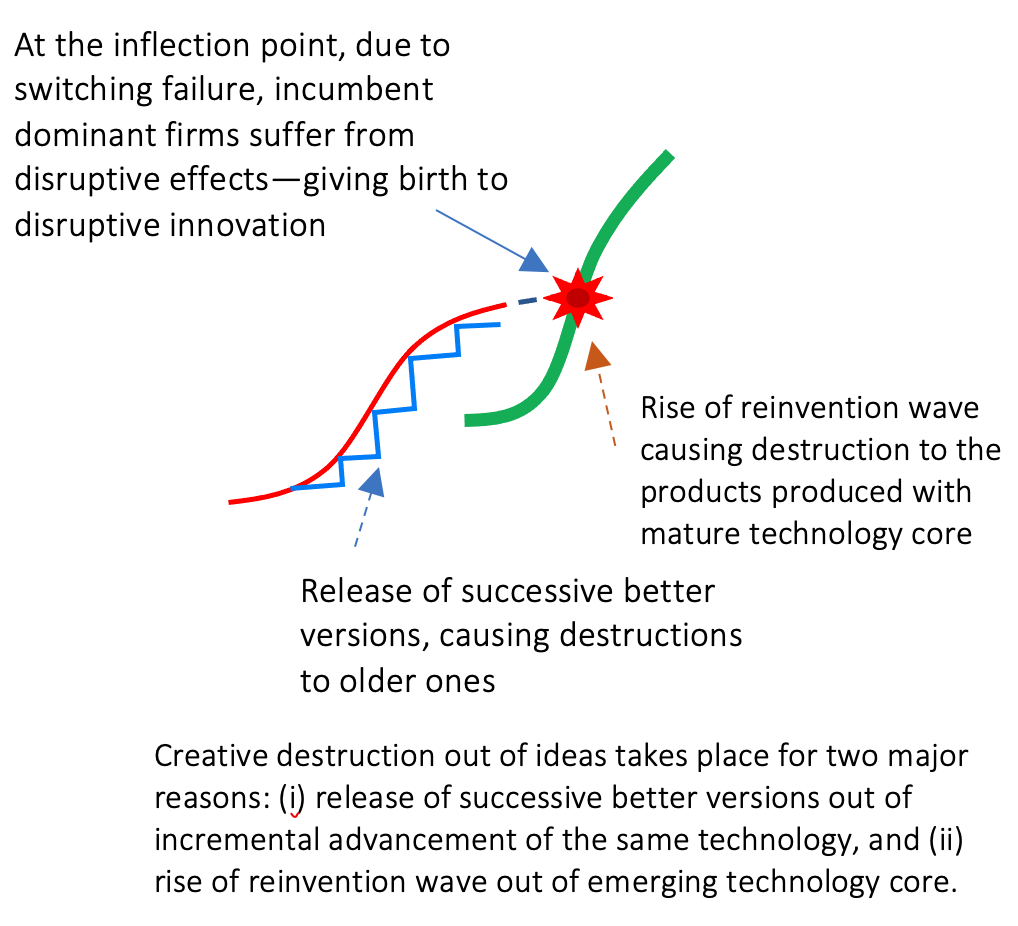

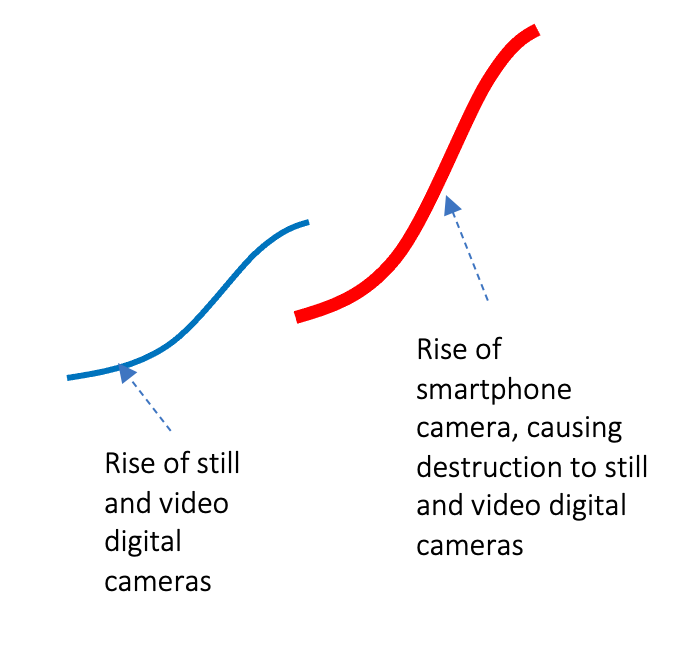

In the journey of pursuing ideas for offering better products at a lower cost, entrepreneurs keep advancing technology core and adding new features as well as advancing existing ones. Invariably, incumbent technology cores start showing signs of flattening out, subsequently leading to maturity. Fortunately, humans’ creative urge does not stop here. The relentless journey of creating ideas for recreating existing means leads to the formation of a new technology core. Entrepreneurs start taking advantage of it in a drive to offer better substitutions to incumbent products. Some of these journeys succeed in making substitution far more attractive to incumbent ones. Subsequently, products around the matured technology core start suffering from plummeting demand. Consequentially, jobs and infrastructure in making and supporting those products also start disappearing. Prof. Schumpeter coined the phrase creative destruction to describe this messy effect of the market economy’s process of benefiting from praxis.

How does creative destruction differ from Christensen’s disruptive innovation?

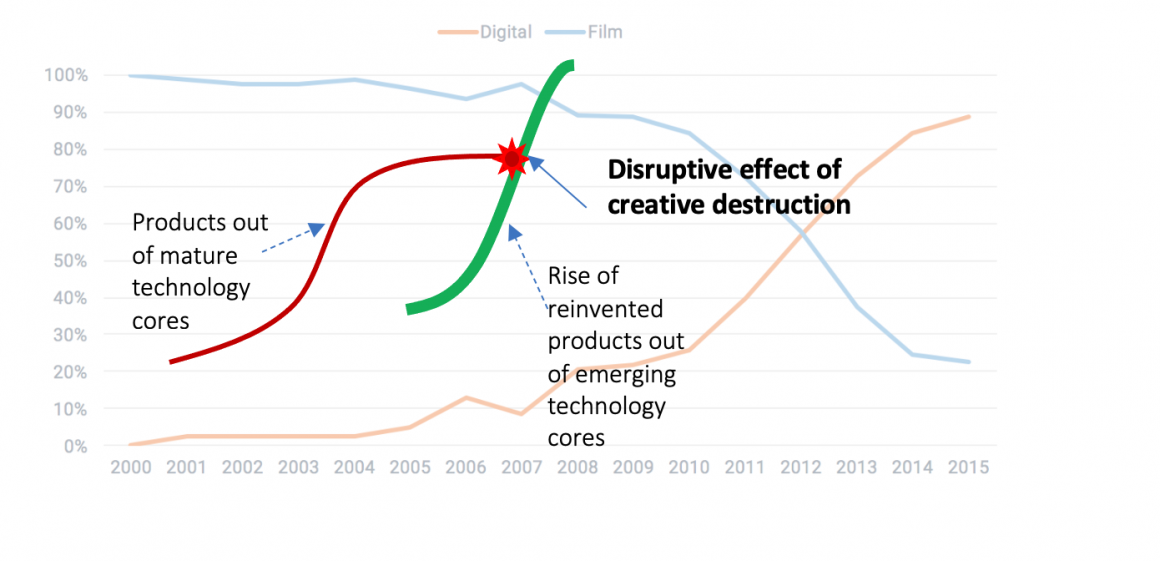

Invariably, creative destruction refers to the obsolesce of incumbent products due to the uprising of a new wave of substitutions. However, not all waves of creative destructions lead to causing disruption to incumbent high-performing firms. There is a fine line between Schumpeter’s creative destruction and Christensen’s disruptive innovation and technology.

Christensen’s disruptive technology and innovation

In the six-page chapter, dedicated to explaining the messy effect of the market economy for offering us prosperity out of innovation, Schumpeter did not offer sufficient clarity. Particularly, how do incumbent firms suffer from disruption due to the uprising of the next wave of innovation around emerging technology core? Why cannot highly successful incumbent firms leverage the uprising next wave, as opposed to becoming victims? Why do invariably risk-taking entrepreneurial firms, start-ups, succeed in disrupting incumbent firms? Incumbent firms, particularly technology ones, often have far more technology, human, financial, and complementary assets than start-ups.

Nonetheless, why do incumbent firms tumble with the uprising of start-ups offering substitutions? It happens to be Prof. Clayton did not get the answer to these and many other pertinent questions in the writing of Prof. Schumpeter on creative destruction. Prof. Christensen’s endeavor to find answers to these questions led to the formation of the theory of “disruptive innovation.”

Christensen’s observations

Prof. Christensen observed that even at the maturity of some products, many potential customers could not deploy them to get their purposes served, in certain situations. By the way, in Christensen’s language, they could not hire those products to get their jobs done. He termed this market, comprising of customers feeling unserved, as nonconsumption. Despite having latent potential, he observed that new technology core often emerges in frail form. Innovative products around them perpetually appear in primitive forms. Consequently, they neither create substitution appeal to incumbent customers nor offer the profit-making opportunity to firms producing matured products around the present technology core. He also observed that incumbent firms often develop monopolistic price-setting capability while posing an extremely high barrier to new entrants. Often this situation entices, perhaps compel, aspiring new entrant (start-ups in contemporary terminology) to take refuse to the emerging technology core.

Technology core must keep progressing to power disruptive innovation

In the beginning, primitive products around emerging technology core fail to create a willingness to pay among customers (both existing and near-future) of incumbent products. Hence, smart start-ups target the nonconsumption segment of the market. To these customers, something is better than having nothing at all. However, due to a very low willingness to pay of the non-consumption market, coupled with the reality of high cost, the early emergence of innovations keeps generating loss-making revenue. In fact, it poses a high challenge to the journey of pursuing substitutions. To increase both willingness to pay and also lower cost, smart start-ups desperately invest in R&D for creating a flow of knowledge and ideas. They also keep building a patent portfolio and complementary assets to leverage those ideas.

Subsequently, with the help of those ideas, they keep adding new features and also improving existing features of the substitutions. In addition to it, they also keep improving production processes. Consequentially, they keep increasing the quality and reducing the cost of their innovations. A winning formula indeed. However, to support this strategy, the technology core must be amenable to rapid growth.

Primitive emergence creates innovators Dilemma, leading to disruptive innovation

At the beginning of the emergence of substitutions around new technology core, incumbent firms do not find any appeal of those primitive products to their existing customers. On the other hand, offering those primitive products to the non-consumption market invariably generates loss-making revenue. Moreover, the uprising of the next wave also poses a threat to their existing profitable products and business models. On top of it, there is also a high risk, as many technology innovation waves do not keep growing succeeding to produce profitable revenue. For example, Honda’s ASIMO retired before commercial rollout. Therefore, the management of high-performing firms, profiting from matured products around proven technology core, faces a dilemma in allocating resources to the next wave. Prof. Christensen coined the phrase ‘innovators dilemma’ to explain this management decision-making predicament. Consequentially, they often delay, sometimes also avoid, allocating resources at the early stage of the next wave.

Disruption takes place due to the failure of switching of incumbent firms

Against the backdrop of the decision dilemma faced by incumbent firms, start-ups pursuing the next wave of technology innovation for offering substitution find no alternative other than vigorously pursuing the journey. They keep (i) fueling R&D, (ii) building a patent portfolio, (iii) building complementary facilities, (iv) developing standards, and expanding complementary goods and services from the 3rd parties, and (v) creating network Externality Effect, among others. Moreover, while substitutions keep experiencing high growth in quality improvement and cost reduction, incumbent products cannot keep pace due to the maturity and natural limitation of the underlying technology core.

Subsequently, the emerging wave of innovation attempts to overtake incumbent products, both in quality and cost. At this point, incumbent firms often take a desperate attempt. Unfortunately, they invariably fail due to the barriers already created by the emerging wave. Due to this reason, along with products around matured technology core, once-dominant firms face ultimate fate—tumbling. For this very reason, Prof. Christensen termed it disruptive innovation. However, a fine line between creative destruction and disruptive innovation also creates confusion and debate. Hence, we should look into details about the theory of Christensen’s disruptive innovation and technology.

Disruptive innovation and technology examples

Of course, innovation waves that cause a disruptive effect on incumbent dominant firms require help from technology cores. They are disruptive technologies. Some of them are internal combustion engine, light-producing filament, Transistor, light-emitting diode, electronic image sensor, graphical user interface, multi-touch, lithium-ion battery, fuel-cells, Humanoid, and many more. Invariably, each of these technologies emerged in a primitive form. In the beginning, each of them was far inferior to the incumbent counterpart. For example, the internal combustion engine was far weaker than the horse. Similarly, the transistor was feebler than vacuum tube technology. Electronic image sensors producing 8×8 black and white noise images were in no way comparable to Kodak’s film.

Nevertheless, they had the hidden potential to keep growing, making innovations increasingly better and cheaper. Start-ups, also existing firms with a start-up approach, pursue them for offering us an array of waves of creative destruction. The list is virtually endless, starting from the filament light bulb, LED bulb, television, digital camera, personal computer, walkman to the smartphone. To our surprise, the uprising of these next waves of innovations caused disruptions to once-dominant firms like RCA, Kodak, DEC, and Nokia, among others. Due to this effect, we have also seen the growth of start-ups as large firms. Some of them are Mercedes Benz, Sony, Intel, Microsoft, and Apple. Christensen’s disruptive innovation and technology theory has been at the core of comprehending such a downfall and the uprising of firms. Invariably to cause disruption, underlying technologies should fuel a megatrend of transformation.

The flow of knowledge and ideas is a must to benefit from disruptive innovations

The uprising of waves of innovations, often disrupting incumbent firms, is at the core of the progression of our quality of living standards in the market economy. This dynamics of the unfolding of successive waves keeps creating discontinuities and instability (known as Schumpeter gale). These discontinuities offer opportunities for start-ups to grow as high-performing firms, often taking over the market of incumbent firms. It also offers the opportunity to the developing countries to enter into the Innovation Economy.

However, there has been a strong role of public policy in financing science and technology R&D for creating the flow of knowledge and ideas. This flow is vital to empower entrepreneurs to pursue a successive wave of innovation for offering us increasingly better alternatives to get our job done better at less. In the absence of public investment for creating and maintaining the flow of knowledge and ideas, the market economy cannot keep progressing by leveraging disruptive innovations, just by offering the freedom of entrepreneurship.